Growing up just west of Louisiana, in East Texas, I know the bayous of Louisiana move slow and deep, and their secrets are hidden deep beneath the surface. The same could be said of my mawmaw. I think of the secrets she’s taking with her as I march behind the jazz band celebrating her life. The music beats a soulful tune, the moan of the trombone and the howl of the trumpet, as we march up the cobblestone road from the funeral home to the cemetery where Maw will be laid to rest. The closer we get to the cemetery, the more joyful the music, now celebrating the life of a woman I lived with almost every summer from age six to sixteen.

Summer in the bayou feels like butter on crawfish, gooey as the sweat rolls down your skin like the butter from the crawfish, and sticky, always sticky. The aroma of full kettles of crawfish boil filled the air from the time I arrived at Maw’s until the end of July. I can almost feel the dirt under my fingernails from digging up red potatoes to clean and boil. And the smell the alligator sausage and crawfish etouffee always cooking in Maw’s kitchen.

I say kitchen, but her house only had three rooms, a great room where the kitchen stretched along one wall, a bedroom, and a bathroom that used to be a bedroom before the landowner installed indoor plumbing. Meemaw (my great grandmother) lived in the tenant house ten feet away, until she didn’t. Maw never spoke of it, but I noticed the broom always placed carefully at the front door no longer stood there either. When I asked, Maw said, “Some t’ings best left alone.” I left it alone, but I wished I’d grilled her.

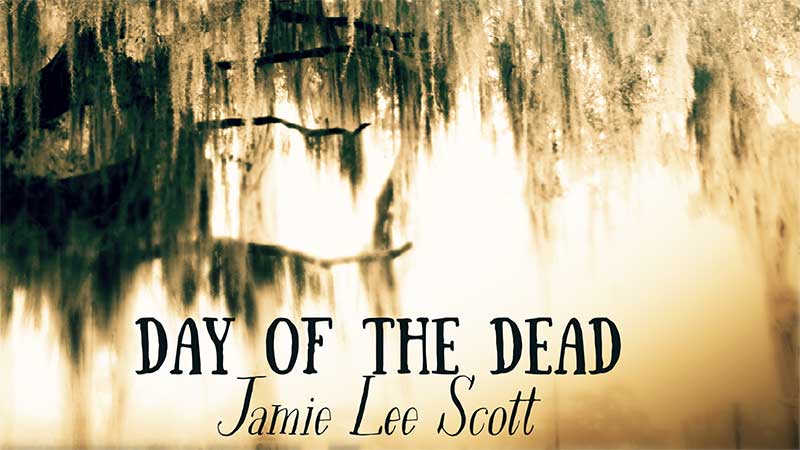

She lived her life in Cajun country, where the blue herons patrol the waters, and live oaks hang heavy with Spanish moss. The cypress trees so old they know the secrets of generations.

Just like the cypress, Maw was old when I was a child, so I always thought of her as ancient. She never changed her ways, adhering to the ways Meemaw taught her, and continuing the practice of hoodoo, as a fourth-generation practitioner. Against my mother’s stern warnings, I learned hoodoo magic from a young age.

My mother couldn’t be bothered to come home to the tenant’s quarters where she grew up an only child sleeping in the same room as her mother. But she often spoke of the trappers’ cabins, adorned with wildlife skulls, pelts of racoons, and brooms, and of the burned out plantation home of which only the kitchen fireplace still stood. She spoke fondly of the ghosts and graves and recalled the vast legends of the swamp. But she refused to return to the ancestral home of her family. I sometimes wonder if she was embarrassed.

As the street surface changes from cobblestone, to asphalt, to gravel, I dance. The spirit of the moment moving me along and dragging long forgotten memories to the forefront.

In the days leading to her ancestralhood (death), I participated in the rituals.

“We be warshing her feet,” Auntie Tommy said. “We release binds keeping Minnie here, making elevations easier.”

Tommy lived in the third tenant house on the plantation, and she danced alongside me. Tommy, like Maw, stood about five feet tall, with a body like the limbs of the cypress tree, narrow but not frail. It did a person well not to test Maw or Auntie Tommy, mistaking tiny for weak.

“After her feet, we warsh her head.” Tommy told me things I already knew.

The head warshing released negative thoughts, and any mental illness Maw may have suffered. But I’m here to tell you, she didn’t entertain negative thoughts and spoke coherently until she could no longer speak.

We spoke often. I worried about her, so I found the best cell tower service and used that company to buy Maw a cell phone.

“Them’s the devil’s doings,” she said, setting the phone on a chair on her porch.

As far as I know, the phone never graced her doorway, but she did answer it when I called. I checked the phone a few days ago, and she’d never used it other than to speak to me. The battery showed one percent. I respect her beliefs, and the phone sits on the chair on the porch as we enter the cemetery.

I smile as the procession ceases, my mind wondering back to my childhood, when things were simpler, and I complained about foraging for wild rice, onions, and edible herbs in the swamps. Maw taught me to collect the Spanish moss, soak it in the river, and dry it for scrubbing pads. I happened to know she used the moss to fill her pillowcases too. The traditions would die with Maw.

I often invited her to visit my world, but she preferred to stay in hers. After I graduated from high school, I didn’t see her as often, considering Maw’s ways ridiculous, and even embarrassing. I regret not visiting. I never told her; I continue my hoodoo ritual practices in the city. I never told anyone, because people tend to mistake hoodoo for voodoo, and I never felt the need to educate them. Hoodoo isn’t a religion, and because I found religion to be lacking on its own, hoodoo filled the gap. My family had core Christian values, which for me had gone by the wayside. But hoodoo felt like part of my soul.

As people and band members disband, Auntie Tommy touches me on the shoulder. “I be leavin’ ya now.”

The sun winks at me as it dips below the horizon. “There’s a full moon, Maw. And can you believe it’s Halloween? You couldn’t have planned this better.” To which I think, she probably did plan it.

I’m alone. “Okay, Maw. I hope you picked the right person for the job.”

I finagle my arm from one of the straps of the backpack I’m carrying, then reach around and pull off the other strap. Setting the pack on the ground, I pull out the items from the altar ritual that started on the plantation.

The garden shovel. This is for the beginning and the end. I stick the shovel in the soft dirt, digging just deep enough for the beer can and mason jar.

“What do I say? Cheers?” I ask the shell of my grandmother, who I can’t see or feel. I pop the top on the beer can, and it fizzes up and over the side of the can, drenching my hand. I switch hands and shake out my wet one, then dry it on my pants. “Cheers, old lady,” I say as I chug the cheap beer.

I look at my notes, to be sure I’m performing the ritual correctly. The notes will go in the Ball mason jar when I’m finished. I won’t share the details of the ritual, but I’ll tell you this, it’s a protection spell. It includes an ancient polaroid photo of Maw and me, eggshells (I break the eggs after drinking the beer and placing the can in the hole I dug). The Polaroid assures the proper person receives the spell. The eggs rid Maw of perceived curses, and the feathers and candle wax, both white, offer blessings. The only thing left in my bag is $1.97 in coins. The last thing on my notes is a name.

Theodore Guidry. The moonlight no longer helps me see, as the live oak trees offer shade from the moonlight. I need the candle, because Maw insisted no flashlights. I consider using the flashlight on my cell phone. No. She didn’t want a cell phone in her house, I won’t use it now. I light the candle and cup my hand around the flame. I only have to relight it four times before I see a headstone with the name Guidry.

Theodore died last year. Wow, I somehow expected this person to have died decades earlier. I jog back to Maw’s grave, leaving the candle lit, I place it on the lid of the mason jar. With not so much as a breeze, the candle stays lit, and the wax melts over the sides. I have to hurry now.

I run back to Theodore’s grave and dig up dirt from just below the headstone. It’s called goofer dirt, and it’s taken from the grave of an extremely powerful person. I wonder what makes Mr. Theodore so powerful. “Thanks Mr. Guidry,” I say as I cup my hand around the loose dirt.

I place the dirt in the mason jar, along with the broken eggshells, polaroid, feathers, my notes, and salt. I repeat the ritual I’ve been practicing and use the wax from the candle to seal the lid tight. I drop the jar in the hole I dug at the foot of Maw’s grave and replace the dirt. “Love you,” I say as I stand and put my shovel back in the backpack. The last thing I do is toss the coins over Maw’s grave. I look up and pray the spirits see my offering.

I don’t even bother to sling the pack over my back as I see my Uber driver at the edge of the cemetery.

Arriving back at Maw’s house, I tip the driver generously. It wasn’t easy to arrange for a driver to pick me up and take me out to the swamp. He didn’t get out of the car and he peels out before he rolls up the window. I laugh.

Someone’s sitting on Maw’s porch. I also see a new blue jar tree. Blue jar trees bring good luck, protection, and peace. I feel my heart lighten, and I swear I hear a whisper in my ear and the brush of someone’s hand on mine. I look down. Nothing.

I plaster on a smile, even though I’m irritated. I want to be alone to celebrate Maw. If I’m honest, she’ll be mad, because I really want to mourn. “Hi, are you a friend of my Maw?”

“Yes, I knew Minnie well. Please, come sit with me.” He’s tall as he stands and gestures to the chair with Maw’s phone sitting on it. He’s also handsome, with coal black skin and white hair trimmed short. He speaks with a heavy Cajun drawl.

I stick my hand out, “I’m Bella Thibodaux.”

He smiles but doesn’t take my hand. His teeth perfect and white; dentures. “Ma’am, I’m Theodore Guidry.”

My phone rings as he says his name, I inhale and choke on my saliva. The caller I.D. reads, Maw. I look down but Maw’s phone isn’t even charged.

Before I have time to process what I’m seeing and hearing, he says, “Welcome home.”

He feels powerful, very powerful indeed, and I feel a shift in the air. We talk until the sun rises, then he leaves (more like he dissipates), and I go inside and curl up with Maw’s pillow.

I wake up with a feeling of completeness I’ve never felt. I call in to my job and quit. Mr. Guidry was right, I’m home.

USA Today bestselling Author, Jamie Lee Scott

Find out about new releases from

BookBub